Published on Oct. 16, 2020

Infectious Bronchitis in Layer Chickens

Infectious bronchitis is an acute, highly contagious upper respiratory tract disease in chickens. In addition to respiratory signs, decreased egg production and egg quality are common, and nephritis can be caused by some strains. Infectious bronchitis virus (IBV), the coronavirus of the chicken, only causes disease in chickens, although the virus has also been found in pheasants and peafowl. Infectious bronchitis is virtually a global disease. Some IBV types (serotypes, genotypes, protectotypes) are widespread, whereas others are regional.

IBV is shed by infected chickens in respiratory discharges (acute phase) and faeces (recovery phase of disease), and it can be spread by aerosol, ingestion of contaminated feed and water, and contact with contaminated equipment and clothing. Secondary bacterial infections with Escherichia coli, Mycoplasma gallisepticum, M synoviae, and/or Avibacterium paragallinarum can aggravate disease.

Clinical Signs

Morbidity for flocks affected by infectious bronchitis is typically 100%. Chicks may cough, sneeze, and have tracheal rales for 10–14 days. Conjunctivitis and dyspnoea may be seen, chicks may appear depressed. Feed consumption and weight gain are reduced.

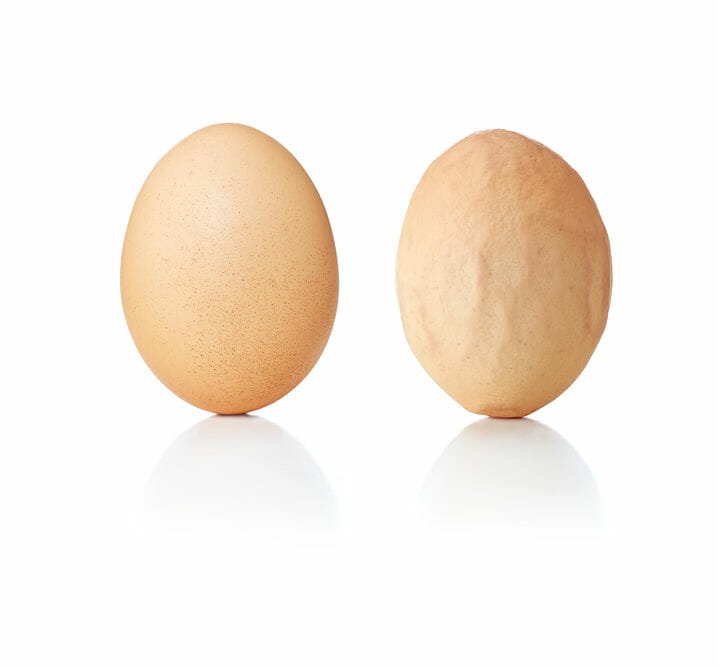

Egg production drops between 3-10% and normally returns to near normal production within one week but drops by as much as 70% can occur. Eggs are often misshapen (pictured below), with thin, soft, wrinkled, rough, and/or pale shells, and can be smaller and have watery albumen. In most outbreaks, mortality is approximately 5%, although mortality rates can be as high as 60% when disease is complicated by concurrent bacterial infection or when nephropathogenic strains induce interstitial nephritis in chicks. Infection of chicks (at 1-2 weeks of age) may cause permanent damage to the oviduct, resulting in layers or breeders that never reach normal levels of production, so-called false layer syndrome.

False laying hens look and ovulate normally but do not produce eggs. Typically, hens appear healthy, with fully developed secondary sexual characters and an active ovary, but a non-functioning oviduct.

Diagnosis

IBV infections can be diagnosed by detection of rising antibody titers by ELISA or HI testing and by virus detection and typing using virus re-isolation or RT-PCR and sequencing.

Typing is necessary to find out which serotype/ genotype is causing the disease.

The extensive use of (live) IBV vaccines complicates diagnosing the disease, because it is not always possible to differentiate a field from a vaccine strain.

Vaccination

Attenuated live and killed vaccines are used to control the disease, but little or no cross reactivity between types requires the correct vaccine type be applied. Revaccination with a different serotype can induce broader protection. Attenuated or adjuvanted inactivated vaccines can be used in breeders and layers to prevent egg production losses as well as to pass protective maternal antibodies to progeny. Eye drop (oculonasal) is the preferred method of live vaccine application, but for mass application often spray or drinking water vaccination is used.

References

- Merck Vet manual.

- J. J. (Sjaak) de Wit and Jane K. A. Cook, Dave Cavanagh, J. Ignjatovic and S. Sapats.

- picture: https://freechickencoopplans.com